Estimated reading time: 8 minutes

When learning vocabulary in a new language, it is quite common to just repeat (over and over and over again) the to-be-remembered word. There are variations to this strategy, and researchers have formalized these variations into what they call massed and spaced practice. Specifically, for massed practice, people simply reiterate the new word without pause. In other words, they cram the word. On the other hand, for spaced practice, individuals will space out its repetition: study the word, wander off to do other things or study other words, and then study the new word again.

In general, people are better at remembering foreign language vocabulary when spacing out repetitions of the new word with time or other information. This learning benefit is known as the spacing effect. Natalie Koval, from Michigan State University, noted that although the spacing effect in second language learning is often replicated, researchers have not addressed its underlying mechanism. A comprehensive understanding of this effect in second language learning would help its optimization.

Memory Research and Second Language Learning

As with second language research, the spacing effect is well established and replicated in the memory field. In fact, Hermann Ebbinghaus first identified the spacing effect in his classic, “Memory: A Contribution to Experimental Psychology,” well over 100 years ago. Memory researchers have suggested a number of theories to account for this effect, one being the deficient processing theory, which highlights two important factors that work in tandem during learning: familiarity (“feeling of knowing”) and attention.

Specifically, the deficient processing theory suggests that for massed practice, a continuously repeated word is maintained in working memory, which leads to high levels of familiarity and, consequently, the allocation of less attention to the word. In contrast, with spaced practice, the last encounter with the new word is not in working memory, which is resource-limited and temporary – time and other information overwrite the last encounter. During the word’s next repetition, because it is not in working memory, the result is a feeling of low familiarity, which leads to increased attention to the word and better memory for the word. The basic underlying assumption is the more attention to a word, the better its learning. Natalie Koval specifically tested whether the deficient processing theory could account for the spacing effect in second language learning.

Second Language Learning Experiment

To this end, Koval devised an experiment that occurred over two days. On day one, she first set up two learning scenarios (massed or spaced repetitions) for novel Finnish words. Then, she tested memory for these words. On day two, she retested retention. A hypothesis from the deficient processing theory is the spaced-out words, as compared to massed or crammed words, would engage more attentional processing and would lead to better retention.

Day One: Learn and Test

Eye Tracking

An EyeLink 1000 tracked participants’ gaze as they studied the novel Finnish words on day one. The main purpose of eye tracking was to collect gaze data (e.g., fixation durations, gaze durations, total reading time to the novel words) as indicators of attention. These eye-tracking metrics allow inferences regarding the amount of attention devoted to studying a foreign language word as a function of learning condition. In each learning condition (massed and spaced), there were 12 unfamiliar Finnish words presented in the context of an English sentence. An example of this is the word “paita” (meaning “shirt”) in this sentence: “Michelle gave Bob a paita for Christmas.” The EyeLink tracked gaze position as participants read these sentences; later, metrics such as gaze duration were computed.

Experimental Trials

Participants knew a test would follow after viewing the unfamiliar Finnish words. Consequently, the task entailed active, deliberate-learning, which mimics natural learning scenarios. Below is a visual of a trial. Each experimental trial began with the English definition of the upcoming Finnish word. A fixation dot followed, and as soon as the participant’s gaze fell on the dot, an English sentence appeared with an embedded Finnish word. After pressing the spacebar, sometimes a comprehension question followed. If this were the case, the participants pressed a “yes” or “no” key to proceed. Then, the next trial began.

Experimental Blocks

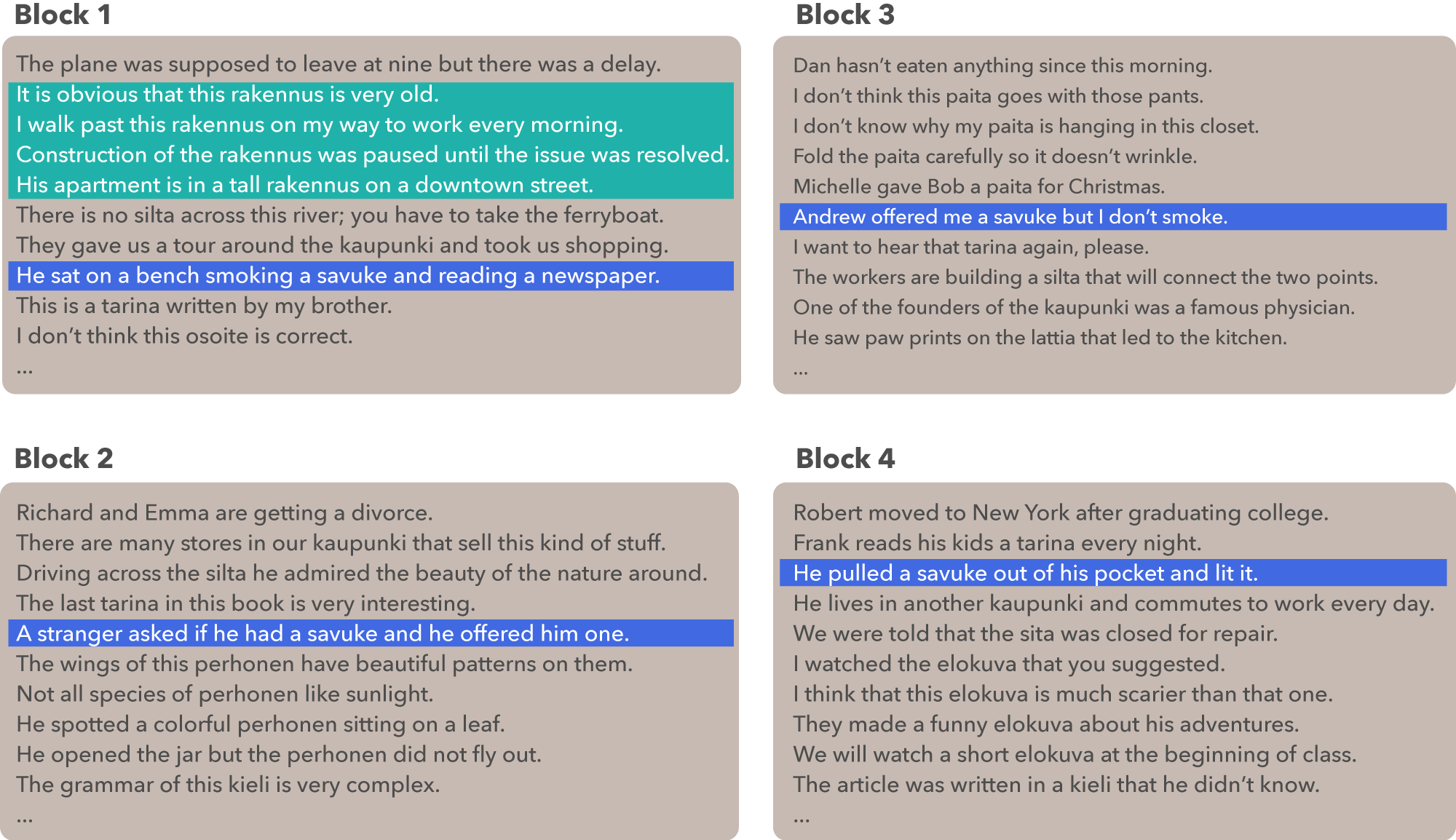

The trials were divided into four blocks. You can see an example of a block below. For the Finnish words in the massed condition, the experimenter repeated a new word in four consecutive sentences (e.g., “rakennus” meaning “building”, see below). In contrast, the space condition consisted of viewing one new Finish word per block across all four block (e.g., “savuke” meaning “cigarette”).

Note, as you can see in the above diagram, the first sentence in each block is completely in English. This is a buffer sentence – a throwaway sentence that addresses potential issues such as initial unpreparedness.

Upon completion of a block, participants performed a math task, which acted as a break and an extra intervening item for spaced repetition learning. Thus, for the spaced condition, two things separated occurrences of a Finnish word: a series of sentences as well as a math distractor task between each block.

Tests for Second Language Learning

Two tests followed this learning and eye-tracking phase to examine retention.

- Recognition Test – Learners picked the correct spelling of each Finnish word among four alternatives. There was also an “I don’t know” option.

- Matching Test – Learners matched the Finnish words with their meanings.

Day Two: Retest

On the second day, either 48 or 72 hours later, the participants redid both tests. The surprise tests were the same as the tests on day one but for the order of the items.

Second Language Learning Results

The Spacing Effect Replicated

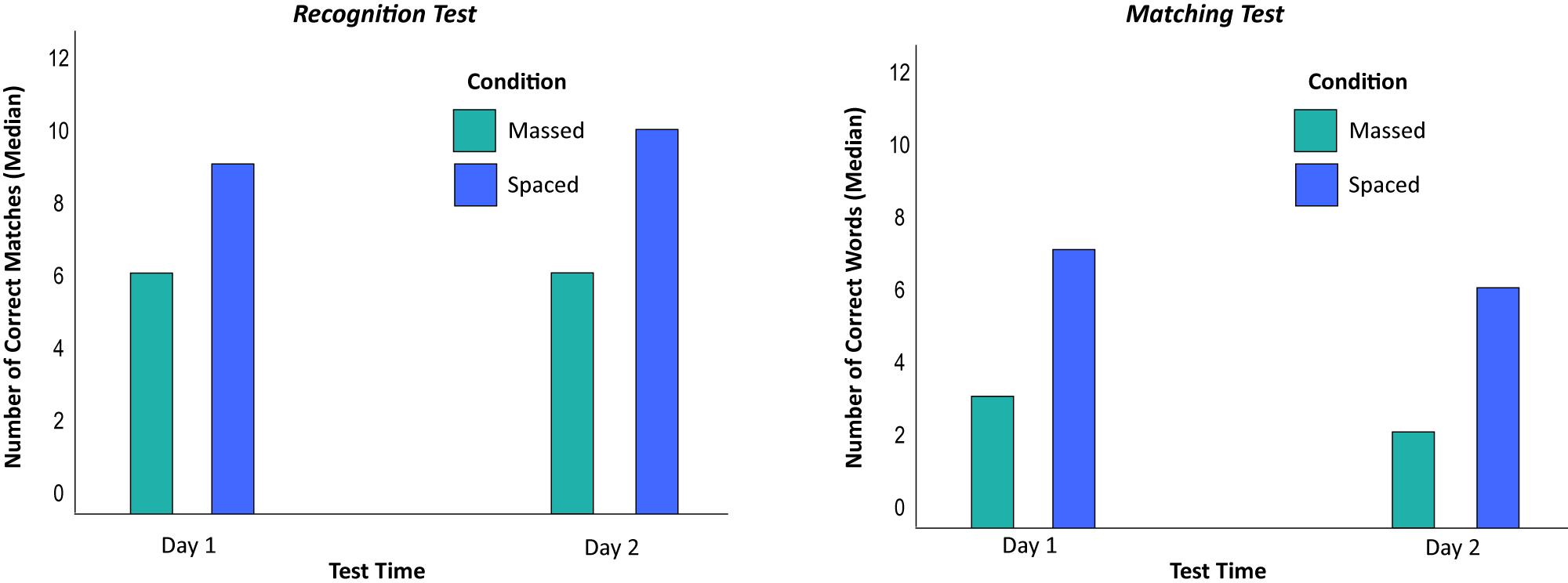

First, the spacing effect must be established. Clearly, this experiment replicated the expected spacing effect (data below); learning benefited more from spacing out a word during practice compared to massed repetition. Both the recognition and matching test scores were higher when the new words were spaced out versus massed together during learning. In addition, this spacing effect was present whether participants took the tests immediately or waited for at least a day after studying.

Eye Tracking Shows Involvement of Attention

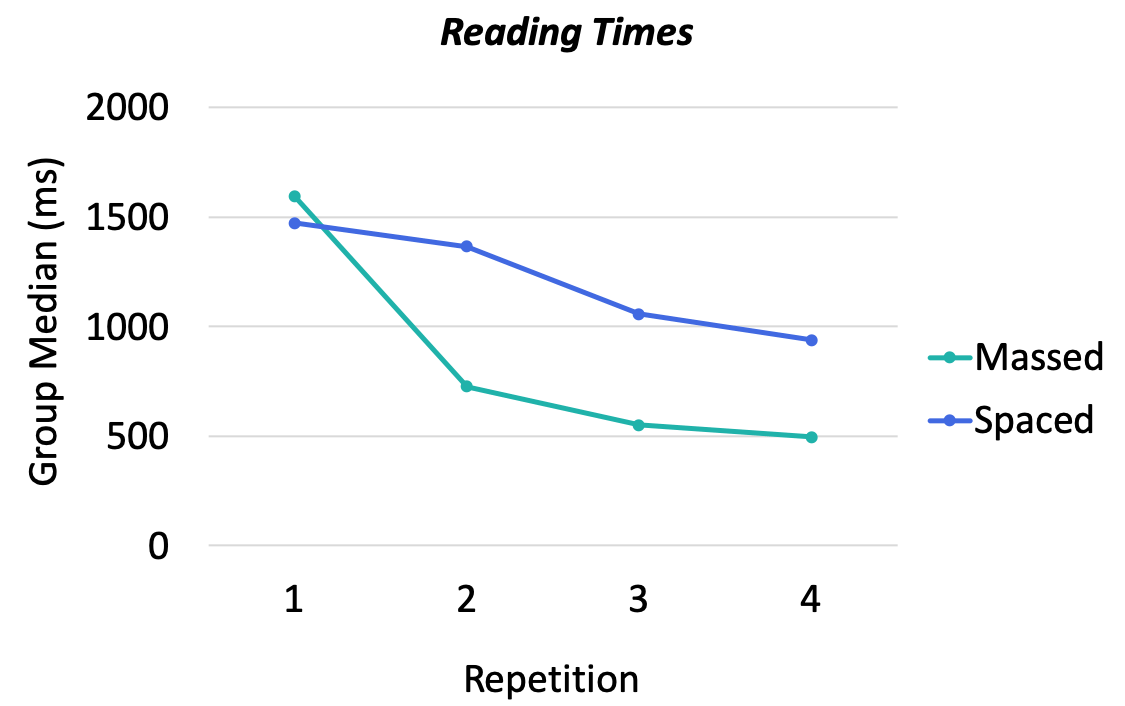

The eye-tracking results underline the importance of attention in spaced versus massed repetition. Specifically, Koval used total reading time as a measure of attention devoted to each Finnish word. (Total Reading Time = Sum of all fixation times on each instance of the Finnish word, including the fixations made during regressions.) The more overt attention directed towards the target, the higher the total reading time.

After the first encounter of each new word, participants attended more to each Finish word if it were spaced out rather than massed in a group (results below). The first time people read a new vocabulary word, whether the word was in the massed or spaced condition, people devoted roughly the same amount of attention regardless of condition. This is unsurprising; there is no difference between the two conditions at this point. As repeated exposures increased, reading time decreased for both conditions. However, those in the space as compared to the massed condition spent significantly more time on the words on the second, third, and fourth exposures.

Koval tested whether the indirect effect of attention (inferred from the total reading times) mediates the direct effect of word spacing on learning (test scores) using a mediation analysis. Recall, the deficient processing theory predicts the positive effects of spacing on learning results from increased attentional processing of spaced versus massed repetitions. Koval’s analysis showed spacing had a significantly positive effect on attention, which had a positive effect on learning, supporting the deficient processing theory.

Second Language Learning Conclusions

From a theoretical perspective, Koval’s research has shown compelling evidence for the replication of the spacing effect with Finnish vocabulary. Further, the eye-tracking data provided strong support for the deficient processing theory. More importantly (arguably), there are practical implications from this work. Some parents, researchers, and educators constantly look for ways to help with second language learning. This study offers some insight and tips. First off, attention is a critical aspect of learning. Increasing attention to a new item results in better learning for the item. Two, the benefit of attention occurs with different types of tests (in this case a recognition or matching test), different levels of test difficulty, and across time. The benefit is not nebulous. Three, increase attention by simply spacing out the practice of new vocabulary. That is to say, avoid massed practice.

“What I particularly like about the effects of spacing study of vocabulary is that this method gets learners to choose to give more attention to the words.”

– Natalie Koval

Contact

If you would like us to feature your EyeLink research, have ideas for posts, or have any questions about our hardware and software, please contact us. We are always happy to help. You can call us (+1-613-271-8686) or click the button below to email:

Eye Tracking Terminology – Eye Movements

Eye Tracking Terminology – Eye Movements