Estimated reading time: 10 minutes

Having the ability to understand things from another person’s viewpoint is critical for successful social interactions and relationships. Theory of Mind research examines this ability to mentalize another person’s thoughts. Specifically, Theory of Mind refers to both the capacity to (a) think about other people’s knowledge, emotions, desires, and intent and (b) understand that other people’s mental states can differ from one’s own. A widely used task in Theory of Mind research is the Sally-Anne false belief paradigm

In this paradigm, Sally and Anne play out scenarios for participants. In a critical scenario, Sally moves a ball to one of two locations and subsequently leaves the room. Then Anne moves the ball to the other location. When Sally returns, participants must indicate where she will search for the ball. In other words, the participants must indicate the location that is consistent with Sally’s belief, as opposed to the updated location. In order to give the “correct” answer and demonstrate Theory of Mind, the participants must realize that they have more information about the ball than Sally, and that in fact, Sally has a false belief about the ball’s location.

New Research in Theory of Mind

Historically, it was thought that Theory of Mind, and the ability to “pass” such false-belief tasks, develop between three and four years of age. More recent research, however, suggests that at least some aspects of Theory of Mind may develop before children’s first birthday. Other recent studies have suggested that adults can engage Theory of Mind processing without awareness of doing so. Notably, when questioned after performing a Theory of Mond task, adults showed no conscious awareness of mentalizing another person’s thoughts, suggesting some cognitive processing in Theory of Mind can be unconscious. A two-pathway account may explain these conflicting results: One pathway is unconscious, automatic, quick, and early-developing – an “implicit” Theory of Mind. The other pathway is conscious, effortful, and later-developing – an “explicit” Theory of Mind.

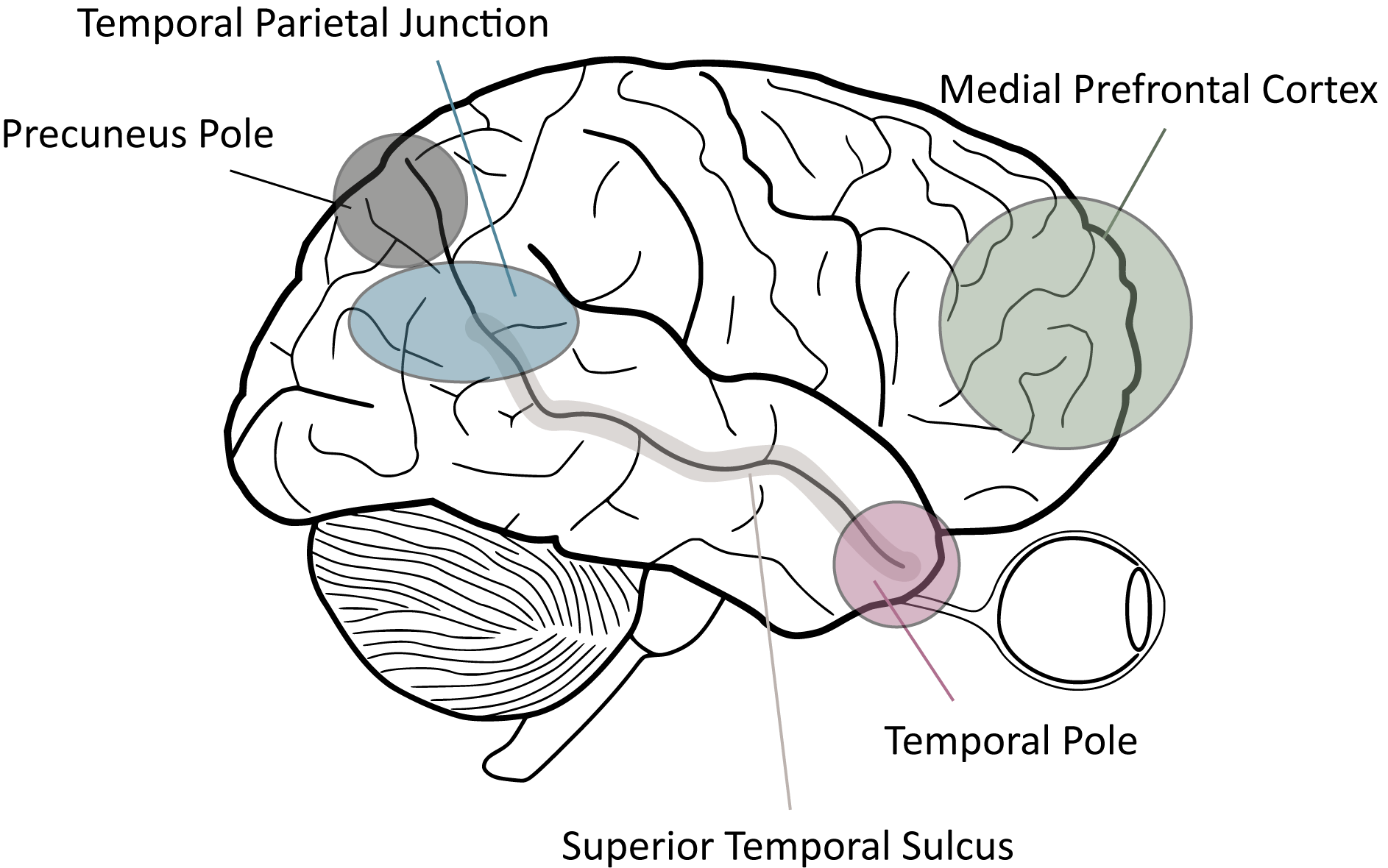

Researchers have highlighted a network of brain regions involved in the explicit, conscious mentalization of another person’s mind (see image below), with the right temporal parietal junction possibly being a core component. Recently, the same network has also been implicated in implicit, unconscious Theory of Mind – but there was no causal evidence connecting the right temporal parietal junction with implicit mentalizing. Indeed, some researchers had even questioned the very existence of implicit Theory of Mind, pointing to the inability of researchers to replicate key findings supporting this construct.

In this blog, we highlight a recent study carried out by Hannah Filmer, Amaya Fox, and Paul Dux at the University of Queensland. Filmer and her colleagues addressed this controversy using an innovative combination of transcranial direct current stimulation, a novel version of the Sally-Anne paradigm, and eye tracking to test for causal evidence for the involvement of the right temporal parietal junction in implicit Theory of Mind. Specifically, eye tracking allowed the experimenters to monitor people’s anticipatory looking behavior during the Sally Ann task after the right temporal parietal junction was disrupted with transcranial direct current stimulation.

Methodology

The authors took some important steps to bolster the study’s transparency and replicability – an important consideration given the controversy in this area:

- They pre-registered the study at the Open Science Framework. The process included explicitly stating the hypothesis, study design, methods, data exclusions, and planned analyses.

- They also combined a well-known implicit task (anticipatory looking Theory of Mind Sally-Anne paradigm) with established eye-tracking technology to test for implicit Theory of Mind.

- They included a questionnaire at the end of the experiment to assess whether participants used explicit or conscious mental processing for the task. If there were any indication of explicit strategies, they excluded the participant’s results.

- They also used stringent Bayesian statistics to assess the results.

Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation

Transcranial direct current stimulation is a non-invasive neuroscientific technique for influencing neural activity that uses constant, low direct electrical current to affect brain neuronal activity. For the process, the positioning of anode and cathode electrodes influences where and how the current flows. Two of the three stimulation protocols affected the right temporal parietal junction in this study:

- Anodal – Positive stimulation increases neural excitability and spontaneous cell firing.

- Cathodal – Negative stimulation decreases neural excitability and spontaneous cell firing.

- Sham – No stimulation. This protocol induced sensations experienced during transcranial direct current without actually influencing neural cell firing.

Anticipatory Looking Theory of Mind Sally-Anne Paradigm

Researchers have used various versions of the Sally-Anne paradigm to study Theory of Mind for over three decades. In this particular experiment, participants watched four types of scenarios play out on a computer. All scenarios began with an actor seated behind a desk with two small boxes. The actor wore a visor in order to avoid inadvertently cueing participants with her eyes. Two scenarios were for the filler trials. In these cases, the video began with a red ball sitting on a box or being placed in one of the boxes and ended with the actor interacting with the ball. These were used to ensure the participants knew the goal of the actor was to interact with the ball.

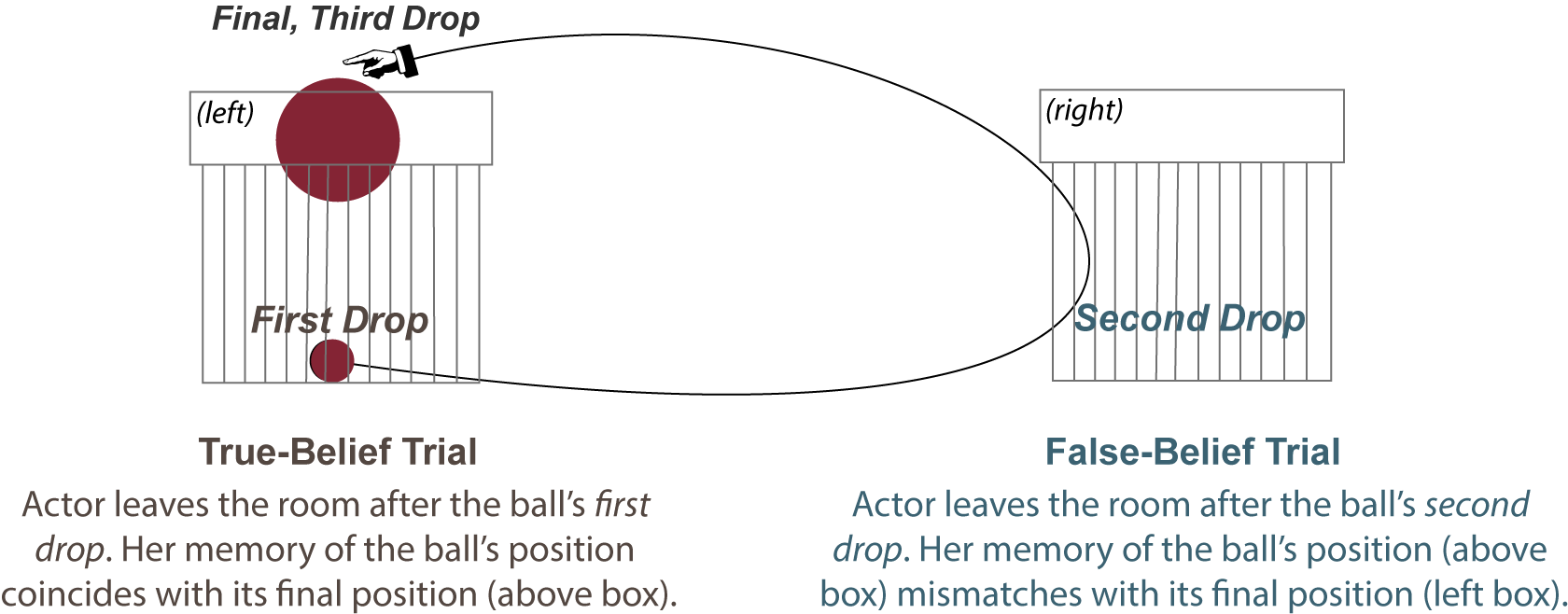

The other two scenarios were the critical trials – the true-belief and false-belief trials. For these trials, the actor watched a puppet move the ball. First, the puppet dropped the ball in the right or the left box. In our example, it is the left box (see image below). Then the puppet moved the ball to the right box. Finally, the puppet returned the ball to the left box. At some point during the scenario, the actor left the room, returning after the last move. The key difference between the true- and false-belief trials was when the actor left the room.

In the true-belief trials, the actor exited after the puppet dropped the ball in the left box, missing the remaining transfers between boxes. Consequently, her memory of the last position of the ball coincided with the final resting position of the ball (left box). Thus, she had a true belief regarding the position of the ball when she came back. In the false-belief trials, the actor exited after the second transfer between boxes. She last witnessed the ball in the right box. Thus, when the actor returned, she had a false belief regarding the location of the ball. She believed the ball was still in the right box because she did not witness the transfer back to the left box.

Procedure

Overall, the task consisted of 40 filler trials, 10 true-belief trials, and 10 false-belief trials. After going through one of the three different transcranial direct current stimulation protocols, each trial began with a fixation cross followed by a video. While the participants watched the video, their main task was to differentiate between high and low-frequency tones as quickly and accurately as possible. The tone task was included to distract participants from the video to increase reliance on implicit Theory of Mind operations. Throughout this experiment, gaze was tracked with an EyeLink 1000.

Results

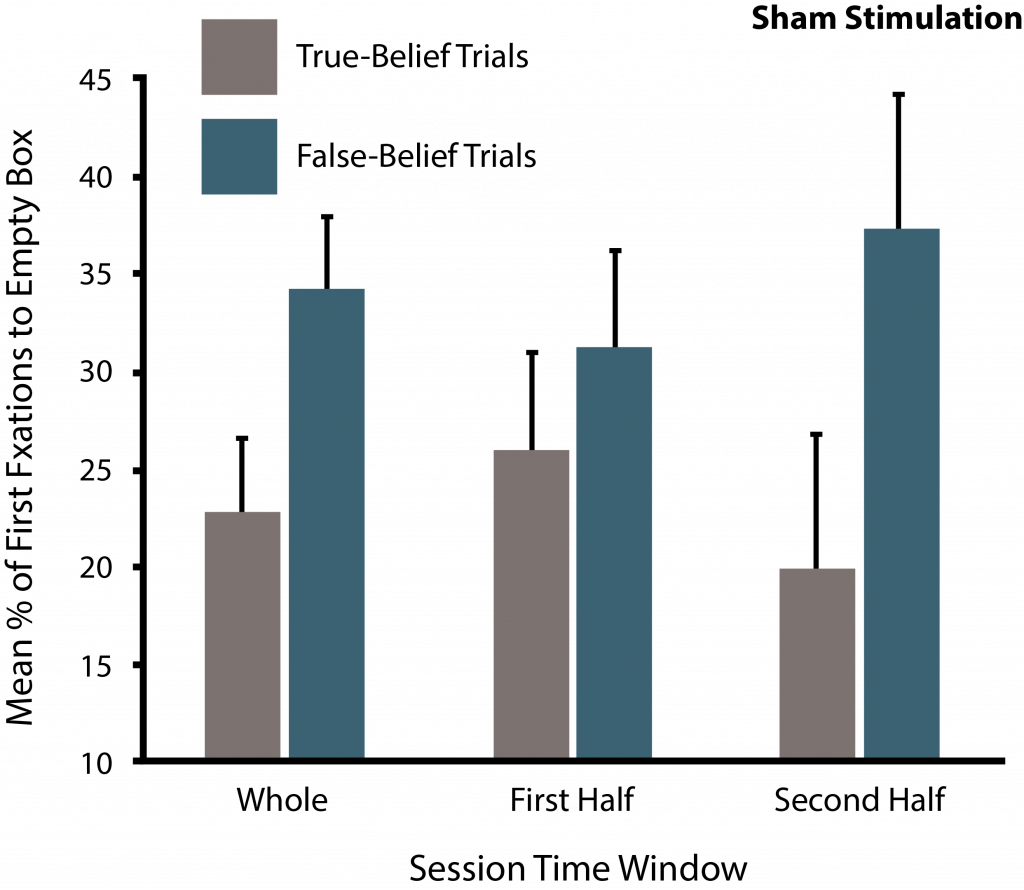

The eye tracker allowed the experimenters to track people’s anticipatory looking behavior to determine if participants could correctly anticipate/forecast the actor’s actions. To this end, the experimenters first established an anticipatory looking period, in this case, after the actor re-entered the room. They then examined whether participants first looked (fixated) at the empty box, the box with the ball, or the actor’s face to determine the percent of first fixations to the empty box as compared to the other two locations.

Evidence for Implicit Theory of Mind under Regular Conditions

If participants are mentalizing the actor’s thought processes and anticipating her behavior, first fixations to the empty box should be higher if the actor incorrectly believes the ball is in the empty box (false-belief trial) as compared to correctly believes it is in the other box (true-belief trial). As shown below, in the sham condition, first fixations were higher to the empty box when the actor had a false belief as compared to a true belief regarding the ball’s location. The difference was larger as the experiment went on (i.e., the effect was stronger during the second half as compared to the first half of the trials). These results suggest that, under regular conditions, the participants were spontaneously tracking the mental state of another person.

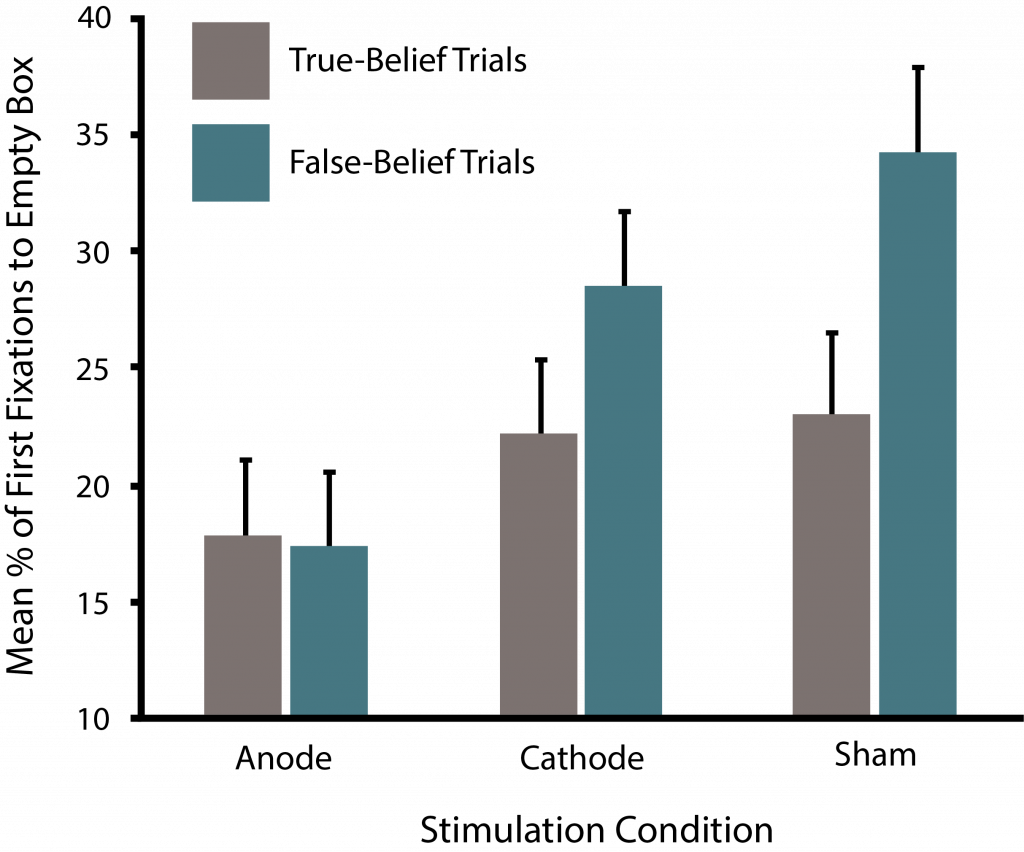

Evidence for Disruption of Implicit Theory of Mind Processing

So what happens to first fixations to the empty box when stimulation is applied to the right temporal parietal junction? If the right temporal parietal junction is implicated in implicit Theory of Mind, the authors predicted that the difference between true- and false-belief trials would change, although they did not make any directional predictions. The results are below. As indicated, there were more first fixations to the empty box in the false-belief condition than in the true-belief condition under sham stimulation. However, no such difference was observed with anodal stimulation; in other words, there was an effect of anodal stimulation on first fixation values, suggesting a disruption of implicit Theory of Mind processing. Examining the results across time, the anodal disruption was evident only in the second half of the trials. The authors suggest that the boredom and fatigue from the stimulation period (which lasted 20 minutes) might have carried over and only reduced after participants engaged in the tone task.

Conclusion

“Theories” about other people’s minds and mental states enable conversations, empathy, and friendships. Consequently, it is important to have the ability to represent another person’s point of view and understand that it can be different from our own. The explicit, conscious processing of another person’s view is well established; however, the idea that people can implicitly understand another person’s perspective has less support. This study provides evidence for this implicit processing – an “implicit” Theory of Mind. Furthermore, the study implicates the right temporal parietal junction as an important neural substrate.

As stated, there have been issues with replicating implicit Theory of Mind results. However, transparent experiments, like this one, will accelerate the process of untangling the conflicting results. Paul Dux, one of the authors of the study, notes:

“Work on the physiological basis of implicit Theory of Mind is still in its infancy. This research is important as it is the first study to provide a casual neural substrate of implicit Theory of Mind. In addition, it’s a large-scale study, with a relatively large sample size and the design and analyses were all preregistered. Thus, one can have high confidence in the results.”

Contact

If you would like us to feature your EyeLink research, have ideas for posts, or have any questions about our hardware and software, please contact us. We are always happy to help. You can call us (+1-613-271-8686) or click the button below to email:

Visual Angle

Visual Angle